-

Table of Contents

- 0. STORY PREFACE

- 1. RABIES - WHAT'S in a NAME?

- 2. RABIES in ANCIENT TIMES

- 3. WHAT IS RABIES?

- 4. LOUIS PASTEUR - EXPERIMENTER

- 5. LOUIS PASTEUR MEETS JOSEPH MEISTER

- 6. A TEEN HERO NAMED JEAN-BAPTISTE JUPILLE

- 7. LOUIS PASTEUR - WORLDWIDE BENEFACTOR

- 8. RABIES as a 21st-CENTURY PROBLEM

- 9. RABIES and ZOMBIES

This image depicts the village of Arbois, in the Jura region of France, where a young Louis Pasteur witnessed horrific treatment of rabies-infected victims. The photo was taken by Christophe Finot on August 12, 2010. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

When I approach a child,

he inspires in me two sentiments:

tenderness for what he is,

and respect for what he may become.

Louis Pasteur

Something terrible must have happened near the village of Arbois, France. Why else are these people screaming so loudly?

Eight-year-old Louis (pronounced "Louie") watches in horror as human beings endure the agony of a red-hot branding iron against their skin. It is the 18th of October, 1831, and the child—son of a local tanner—is traumatized by what he sees.

At least eight individuals have been bitten by a "mad" wolf who’d rampaged the nearby town of Villers-Farley and who also bit some people in Arbois.

Instead of going to a doctor’s office for treatment, bitten individuals go to the blacksmith’s shop. Instead of getting injections (which are commonplace today), patients get a branding iron (to cauterize their bite wounds).

Louis learns this is normal protocol whenever a rabid animal bites someone. Soon he will also learn that such barbaric treatment neither cures nor prevents rabies.

In 1831—and for thousands of years before—anyone who developed rabies from a rabid-animal bite always died. There was no medicine to prevent the disease from developing in humans, and there was no cure.

Put differently, if people actually developed rabies from the bite of a rabid animal, they had a zero-percent chance to survive. Worse ... they were assured of horrific pain and suffering before dying.

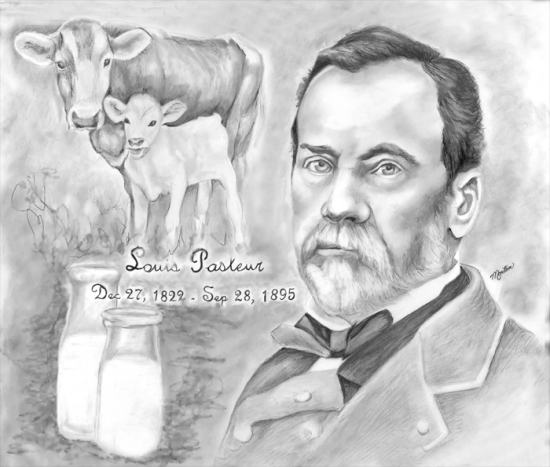

As the years pass, the young lad from the French village—Louis Pasteur—becomes famous for developing life-saving processes (like a vaccine for anthrax and pasteurization for milk). He never forgets, however, what he saw that day in the blacksmith shop.

Fifty years later, in 1885, he gets his chance to do something about it.

First Chapter

First Chapter