-

Table of Contents

- 0. STORY PREFACE

- 1. RABIES - WHAT'S in a NAME?

- 2. RABIES in ANCIENT TIMES

- 3. WHAT IS RABIES?

- 4. LOUIS PASTEUR - EXPERIMENTER

- 5. LOUIS PASTEUR MEETS JOSEPH MEISTER

- 6. A TEEN HERO NAMED JEAN-BAPTISTE JUPILLE

- 7. LOUIS PASTEUR - WORLDWIDE BENEFACTOR

- 8. RABIES as a 21st-CENTURY PROBLEM

- 9. RABIES and ZOMBIES

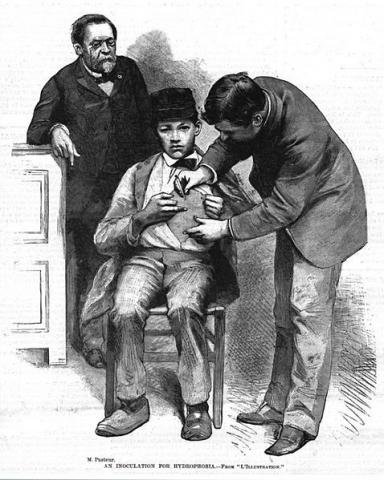

L’Illustration, a French newspaper, originally published this drawing of Jean-Baptiste Jupille receiving a rabies vaccination administered by a member of Pasteur’s team while Pasteur himself witnesses the event. The image, as depicted here, was also published by Harper’s Weekly in its December 19, 1885 issue.

Pierre-Joseph Perrot, the mayor of Villers-Farley, sent an urgent letter to Louis Pasteur which the famous scientist received on October 17, 1885. The Mayor had a request.

Could Monsieur Pasteur please care for a 15-year-old shepherd who’d saved the lives of six younger shepherds from being bitten by a rabid dog? Pasteur agreed, and Jean-Baptiste Jupille—who had extensive bites on both of his hands—was on the next train to Paris.

Pasteur began Jean-Baptiste’s treatments on the 20th of October, 1885 with one shot per day. On the sixth day of the treatment protocol, Pasteur presented a paper to the French Academy of Sciences.

Among other things, he told his distinguished colleagues about the young man’s heroic acts:

The Academy perhaps cannot hear without emotion the account of the courageous act and the great spirit of the young man which I have begun to treat last Tuesday.

This is a villager, of 15 years, his name Jean-Baptiste Jupille, of Villers-Farlay (Jura), who seeing a dog of suspect bearing, of strong stature, threw himself on a group of six of his little friends, all much younger than himself, threw himself, armed only with his whip, in front of the animal.

The dog seized Jupille by the left hand. Jupille then threw the dog to the ground, held him beneath him, opened his jaws with his right hand in order to free his left hand, not with receiving many new bites, then with the cord of his whip, he muzzled him and striking him with his shoes, killed him.

Although six days had passed before Pasteur could begin his first treatment, he believed that Jean Baptiste had a good change to survive. Pasteur continues with his words to the Academy:

After, I may say, innumerable experiments, I have at last found a method ... that has already proved successful in the dog so constantly in so many cases that I feel confident if its general applicability to all animals and to man himself.

One of the Academy’s members, utterly moved by Pasteur’s report, asked the esteemed organization to award Louis the national prize for virtue. Such a request was understandable, given how many people were dying annually because of rabies.

In London, for example, 29 people had died of “hydrophobia”—an alternative name for rabies—during the first weeks of 1877. A “Rabies Order” allowed police officers in that city to aggressively manage (or dispose of) stray dogs to combat “rabies of the streets.”

Soon after word spread about Pasteur’s vaccination, which saved the lives of Joseph Meister and Jean-Baptiste Jupille, hundreds of people came to see the great scientist. For the first time, in the history of the world, people who were bitten by rabid animals no longer had to die if they were able to get vaccinated before the rabies virus reached their nervous system.

A group of Russian peasants, who’d been mauled by a rabid wolf, also came to see Pasteur in Paris. Traveling the long distance from Smolensk, some of the victims had been so ravaged by the wolf they could hardly walk. Their leader knew a single French word: “Pasteur.”

Because of the travel time, two weeks had passed before the Russians reached Paris. Learning this, Pasteur changed his treatment protocol to innoculate the Russians twice each day.

All but three of the injured survived. When the Russian Tsar learned about Pasteur’s effective vaccine, and the impact it had (and would continue to have) on Russian lives, he awarded Pasteur with the Diamond Cross of St. Anne.

To aid Pasteur in his work, supporters began an international fund-raising effort. Donations poured in from around the world, including from the Russian Tsar who donated one hundred thousand francs.

On the 14th of November, 1888, Pasteur was on hand to dedicate the new Pasteur Institute in Paris. After he grew-up, Joseph Meister—the first person to be saved by Pasteur’s rabies vaccine—became a guard at the Institute. He kept that job until the day Paris fell to the Nazis.

Entering the Institute, the invaders demanded access to Pasteur’s crypt, but Joseph refused. After the Nazis broke into the crypt, despite his pleas to the contrary, Meister shot himself.

Today there are branches of the Paris-based Pasteur Institute in various cities around the world. More than a century after his death, Pasteur—a humble man, despite all of his fame—remains one of the world’s greatest benefactors.

-

Table of Contents

- 0. STORY PREFACE

- 1. RABIES - WHAT'S in a NAME?

- 2. RABIES in ANCIENT TIMES

- 3. WHAT IS RABIES?

- 4. LOUIS PASTEUR - EXPERIMENTER

- 5. LOUIS PASTEUR MEETS JOSEPH MEISTER

- 6. A TEEN HERO NAMED JEAN-BAPTISTE JUPILLE

- 7. LOUIS PASTEUR - WORLDWIDE BENEFACTOR

- 8. RABIES as a 21st-CENTURY PROBLEM

- 9. RABIES and ZOMBIES

Back

Back

Next Chapter

Next Chapter

Back

Back

Next Chapter

Next Chapter