On the 23rd of March, in 1775, a man called Patrick Henry took the floor of a meeting held at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia. The meeting had a formal name—the Second Virginia Convention.

The first shots of the American Revolution had not-yet been fired, when Patrick Henry gave this speech, but they were not far off.

Patrick Henry was a speaker who was really good on his feet. He was masterful at posing rhetorical questions and could craft a speech, on the spot, without notes. He was able to mix verbal firing power with reasoned inquiry and understood the subjects he addressed (including viewpoints opposed to his own).

He knew why the American Colonies needed to revolt against Britain and was able to clearly and skillfully articulate his reasons. His speeches were clear and concise, and he chose his words carefully.

Above all, he believed in liberty. He wanted liberty not just for his country, but for individuals living within that country. He was fearless when it came to stating his positions (even when he knew those positions, and his words, might offend others).

People listened to what Patrick Henry said because he had such a great way of making his points. He was able to inspire a room filled with people who did not always agree on everything (or even with him).

The speech he gave on March 23rd, 1775, is his most-famous. Beyond his personal legacy, “Liberty or Death” helps people to understand the reasons (and passions) which fueled the Colonists’ desire to break-free of British rule.

It wasn’t just semantics for Patrick Henry. He knew that his words were an actual call-to-arms. He recognized that hoping for peace, by submitting to Parliament and the British Crown, was just an illusion by March of 1775.

Hereafter is the speech which remains one of America’s most famous:

NO man thinks more highly than I do of the patriotism, as well as abilities, of the very worthy gentlemen who have just addressed the House. But different men often see the same subject in different lights; and, therefore, I hope that it will not be thought disrespectful to those gentlemen, if entertaining, as I do, opinions of a character very opposite to theirs, I shall speak forth my sentiments freely, and without reserve.

This is no time for ceremony. The question before the House is one of awful moment to this country. For my own part, I consider it as nothing less than a question of freedom or slavery. And in proportion to the magnitude of the subject, ought to be the freedom of the debate. It is only in this way that we can hope to arrive at truth and fulfill the great responsibility which we hold to God and our country.

Should I keep back my opinions at such a time, through fear of giving offense, I should consider myself as guilty of treason towards my country and of an act of disloyalty towards the majesty of Heaven which I revere above all earthly kings.

Mr. President it is natural to man to indulge in the illusions of hope. We are apt to shut our eyes against a painful truth - and listen to the song of the siren [a reference to Homer’s epic tale, The Odyssey] till she transforms us into beasts. Is this the part of wise men engaged in a great and arduous struggle for liberty? Are we disposed to be of the number of those who, having eyes, see not, and having ears, hear not, the things which so nearly concern their temporal salvation? For my part, whatever anguish of spirit it may cost, I am willing to know the whole truth; to know the worst and to provide for it.

I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided; and that is the lamp of experience. I know of no way of judging of the future but by the past. And judging by the past, I wish to know what there has been in the conduct of the British ministry for the last ten years to justify those hopes with which gentlemen have been pleased to solace themselves and the house?

Is it that insidious smile with which our petition has been lately received? Trust it not, sir; it will prove a snare to your feet. Suffer not yourselves to be betrayed with a kiss. Ask yourselves how this gracious reception of our petition comports with these warlike preparations [by the British] which cover our waters and darken our land.

Are fleets and armies necessary to a work of love and reconciliation? Have we shown ourselves so unwilling to be reconciled that force must be called in to win back our love? Let us not deceive ourselves, sir. These are the implements of war and subjugation - the last arguments to which kings resort.

I ask gentlemen, sir, what means this martial array if its purpose be not to force us to submission? Can gentlemen assign any other possible motives for it? Has Great Britain any enemy, in this quarter of the world to call for all this accumulation of navies and armies? No, sir, she has none. They are meant for us: they can be meant for no other. They are sent over to bind and rivet upon us those chains which the British ministry have been so long forging.

And what have we to oppose to them? Shall we try argument? Sir, we have been trying that for the last ten years. Have we anything new to offer on the subject? Nothing. We have held the subject up in every light of which it is capable; but it has been all in vain.

Shall we resort to entreaty and humble supplication? What terms shall we find which have not been already exhausted?

Let us not, I beseech you, sir, deceive ourselves longer. Sir, we have done everything that could be done to avert the storm which is now coming on. We have petitioned - we have remonstrated - we have supplicated - we have prostrated ourselves before the throne, and have implored its interposition to arrest the tyrannical hands of the ministry and Parliament.

Our petitions have been slighted; our remonstrances have produced additional violence and insult; our supplications have been disregarded; and we have been spurned, with contempt, from the foot of the throne.

In vain, after these things, may we indulge the fond hope of peace and reconciliation. There is no longer any room for hope. If we wish to be free - if we mean to preserve inviolate those inestimable privileges for which we have been so long contending - if we mean not basely to abandon the noble struggle in which we have been so long engaged, and which we have pledged ourselves never to abandon until the glorious object of our contest shall be obtained - we must fight!

I repeat it, sir, we must fight! An appeal to arms and to the God of Hosts is all that is left us!

They tell us, sir, that we are weak - unable to cope with so formidable an adversary. But when shall we be stronger? Will it be the next week, or the next year? Will it be when we are totally disarmed, and when a British guard shall be stationed in every house? Shall we gather strength by irresolution and inaction? Shall we acquire the means of effectual resistance by lying supinely on our backs, and hugging the delusive phantom of Hope, until our enemies shall have bound us hand and foot?

Sir, we are not weak, if we make a proper use of the means which the God of nature hath placed in our power. Three millions of people, armed in the holy cause of liberty, and in such a country as that which we possess, are invincible by any force which our enemy can send against us.

Besides, sir, we shall not fight our battles alone. There is a just God who presides over the destinies of nations, and who will raise up friends to fight our battles for us. The battle, sir, is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave.

Besides, sir, we have no election. If we were base enough to desire it, it is now too late to retire from the contest. There is no retreat, but in submission and slavery! Our chains are forged, their clanking may be heard on the plains of Boston! The war is inevitable - and let it come!

I repeat it, sir, let it come!

It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry, peace, peace - but there is no peace. The war is actually begun. The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have?

Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!

The Colonies came to stand with Patrick Henry in his quest for liberty. Many died, over many years, as the Revolution dragged on. But when the last “Redcoat” left American territory, the new and independent country was free of British rule.

Now ... for the rest of the story.

Patrick Henry’s speeches were mostly extemporaneous. He didn’t use notes. There wasn’t a court reporter taking down his every word.

So ... how do we know that the words we read today are the words he actually said when he gave his speeches?

Enter... William Wirt, a man who wanted to write a biography of Patrick Henry.

When he was 32 years old, Wirt was a practicing lawyer in Virginia. It was 1805, and Patrick Henry was dead. (He died not long before the century turned.)

Without written words and a written record, Wirt began his self-imposed task of creating Patrick Henry’s biography. It would not be easy.

Ten years into the process, Wirt was still searching for reliable resources. He told a friend:

It was all speaking, speaking, speaking. ’Tis true he could talk— ‘Gods how he could talk!’ but there is no acting ‘the while.’ …And then, to make the matter worse, from 1763 to 1789, covering all the bloom and pride of his life, not one of his speeches lives in print, writing or memory. All that is told me is, that on such and such an occasion, he made a distinguished speech…. [T]here are some ugly traits in H’s character, and some pretty nearly as ugly blanks. He was a blank military commander, a blank governor, and a blank politician, in all those useful points which depend on composition and detail. In short, it is, verily, as hopeless a subject as man could well desire. (See Memoirs of the Life of William Wirt, Volume 1, by John Pendleton Kennedy at page 345.)

Wanting to use primary sources, Wirt searched and searched, but where would he find what he needed? Sources seemed elusive to this erstwhile biographer:

“Fettered by a scrupulous regard to real facts,” he confessed, felt “like attempting to run, tied up in a bag.” (See Memoirs of the Life of William Wirt, Volume 1, by John Pendleton Kennedy at page 344.)

The best he had, by 1815—and in the years preceding—were fading memories possessed by aging men. Were they reliable? How could those memories help Wirt to get the facts straight? How could they help him to put exact words into Patrick Henry’s mouth?

Only one chap—Judge St. George Tucker—tried to give Wirt an exact account of Henry’s words, but he had no notes and not a single shred of paper to support his memory. He supplied Wirt with just a part of the famous speech (which those present agreed had greatly inspired them):

Let us not, I beseech you, sir, deceive ourselves longer. Sir, we have done every thing that could have been done, to avert the storm which is now coming on. We have petitioned—we have remonstrated—we have supplicated—we have prostrated ourselves before the throne, and have implored its interposition to arrest the tyrannical hands of the ministry and parliament. Our petitions have been slighted; our remonstrances have produced additional violence and insult, our supplications have been disregarded; and we have been spurned, with contempt, from the foot of the throne. In vain, after these things, may we indulge the fond hope of peace and reconciliation. There is no longer any room for hope. If we wish to be free—if we mean to preserve inviolate those inestimable privileges for which we have been so long contending—if we mean not basely to abandon the noble struggle in which we have been so long engaged, and which we have pledged ourselves never to abandon, until the glorious object of our contest shall be obtained—we must fight!—I repeat it sir, we must fight!! An appeal to arms and to the God of Hosts is all that is left us!

What about the “peace when there is no peace” line? Wirt took that from another witness—Edmund Randolph—who had heard Patrick Henry’s speech and published an article about it, during 1815, in the Richmond Enquirer.

Randolph also wrote about the impact of Henry’s speech on his audience:

No other member…was yet adventurous enough to interfere with that voice which had so recently subdued and captivated. (See The True Patrick Henry, by George Moran, at page 196.)

A Baptist minister, who had observed the speech, recalled:

I felt sick with excitement. Every eye yet gazed entranced on Henry. Men were beside themselves. (See Quarterly Review of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, Volume 11, Issue 1, at page 48.)

Colonel Edward Carrington, another person who had watched the proceedings—from the outside of the church, looking-in through a church window—was so moved by Henry’s speech that he declared, to his fellow spectators:

Let me be buried at this spot! (See The Presbyterian and Reformed Review, Volume 3, 1892, edited by Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield, at page 393.)

He was, decades later, when his widow honored his request.

It was up to William Wirt—himself a leading orator of his day—to get the whole speech down on paper. The lead prosecutor in Aaron Burr’s treason trial, Wirt also became America’s Attorney General (when James Monroe was President). It is little wonder, then, that Patrick Henry’s speech, as we know it, reflects a skilled orator’s cadence and pace.

But of the 1,217 words in the “Liberty or Death” speech, more than a thousand came from Wirt. He did the best he could to rely on firsthand sources and to construct, for posterity, the Revolution’s most-galvanizing speech (which was never contemporaneously recorded in its entirety).

To read William Wirt’s account, of Patrick Henry’s speech, see pages 119-123 of Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry: Electronic Edition (online via Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, via Documenting the American South).

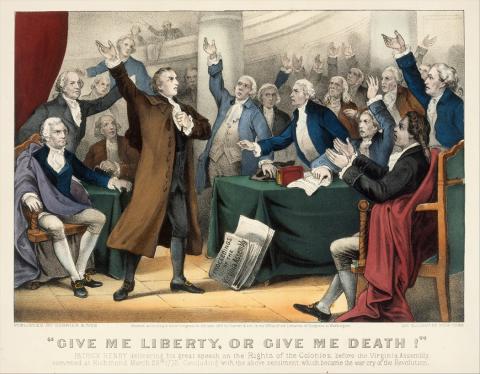

This lithograph, by Currier & Ives, is from 1876. Its caption reads: "Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death!"

Click on the image for a better view.

Media Credits

Lithograph, by Currier & Ives, from 1876. Its caption reads: “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death!–Patrick Henry delivering his great speech on the Rights of the Colonies, before the Virginia Assembly, convened at Richmond, March 23rd, 1775. Concluding with the above sentiment, which became the war cry of the Revolution.” Online via the Library of Congress. Public Domain.